I was living in Winnipeg; I’ve spent my whole life here. I was diagnosed at the age of 6, spring of 1974, it was the May long weekend. I was not terribly sick but was showing signs: eating a lot, urinating a lot, etc. My mom had a doctor’s appointment and she brought me with her, and the family doctor recognized the symptoms and suggested she take me to the hospital, he met us there and that’s when I received my diagnosis.

My first thought as a child was regret that I hadn’t eaten the ice cream on the hospital tray, thinking I would never be able to eat it again.

I also very clearly remember a nurse showing me how to inject a needle into an orange. She also let me inject her! I learned very early and right away how to administer needles on myself.

From a child’s perspective, being at school with diabetes was not a challenge because I only took insulin once a day, at breakfast. I went home for lunch. I didn’t do anything that showed I had diabetes. I didn’t have many low blood sugars (hypoglycemia). But each one was a crisis. Every low was an acute low. And it really was “feeling” low – unless you were so low you had physical symptoms. There was no test to identify if I was low, or how low or how long I had been low. I would drink orange juice that we added sugar to, because the risk from a low was so much greater. Now, if I go low, I can eat a few jellybeans or have some sips of juice, because of the information I receive from my CGM (continuous glucose monitor).

I started blood testing as a teenager in the 1980’s. Before that I tested for sugar in my urine using a test tube and a tablet. Later on, there were test strips. I tested in the morning, evening and before bed. Testing felt like a wasted effort because the results were the same all the time. And there was nothing to do about the results, except record them.

Now, I wear a sensor that provides information to an insulin pump that adjusts my basal rate based on the results. What incredible progress!

For the first 10 years after I was diagnosed, I went to the doctor’s office, maybe monthly. He took blood out of my arm and got the same information my sensor provides every five minutes. Except he only had one result a month and would have to determine if my insulin needed to be changed based on that single result. Insulin was also incredibly different. At that time insulin was made from cattle or pig pancreases. There was only short acting, long acting or a mixture of the two (insulins). There was no such thing as a correction dose. You had no way to know if your insulin was right or wrong, all you were really doing was keeping yourself alive with insulin, to prevent wasting (starving).

Diabetes was managed primarily through strict adherence to a diet. I stopped eating peanut butter as a child because there was sugar added to it. The dietician that my family went to gave us a recommended number of “food exchanges” I should eat. It was all about eating the same number of ‘exchanges’ at breakfast each day. The same applied to lunch, afternoon snacks and dinner. There was no carb counting because there was no variability. There was no glycemic index.

Another thing I remember from my life as a kid with T1D was ‘cheating’. ‘Cheating’ was eating outside my diet. For example, Halloween candy. This was especially a problem around Halloween or Easter if there was a lot of candy or chocolate around the house. The advice to deal with the impact of having eaten the candy was to go for a walk. We now know that exercise with high blood glucose doesn’t bring it down immediately. You won’t feel the results for a few hours. But that was unknown at the time.

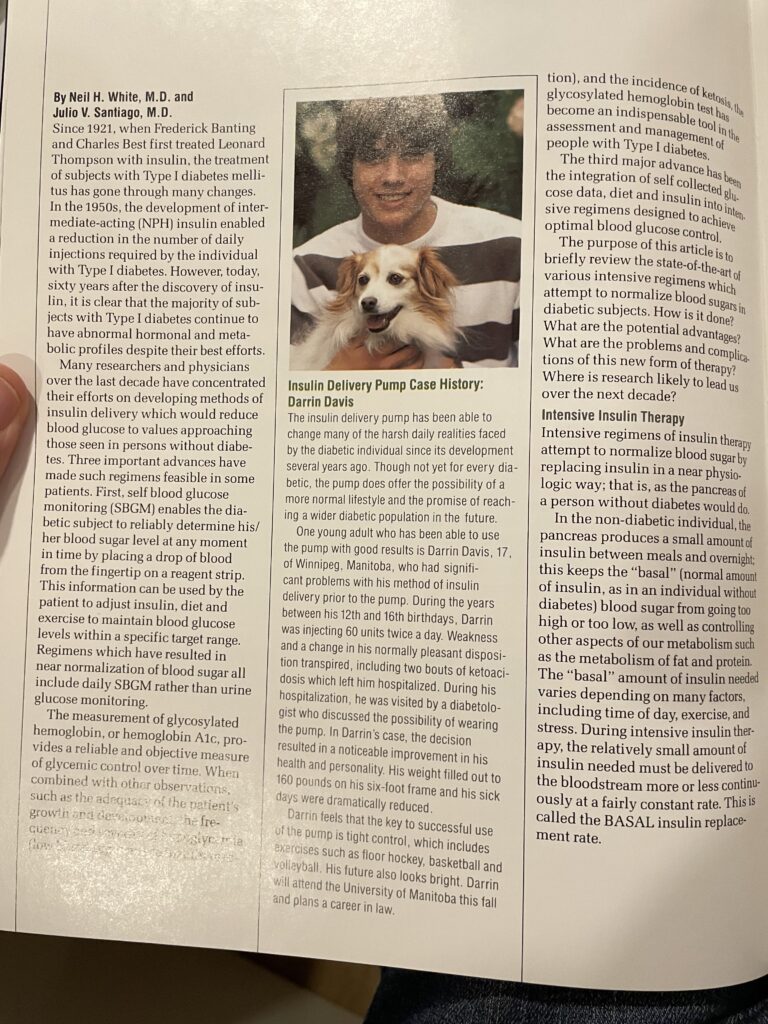

I went on a pump at 16 because I wasn’t well-managed at the time. My HbA1c was 18. The pump then was the size of an iPhone Max but about three times as thick. There was no way to hide it. Fortunately, I am a gregarious person, and I became comfortable with it. At least to some degree. When I took a break from my pump in my mid-20s and went to multiple daily injections, I would go to the bathroom to take my insulin, if I was in a restaurant. But then I realized (again) I didn’t have to hide it. When I stopped doing that, lo and behold the world didn’t stop moving. It was fine. People weren’t watching me. Mostly they didn’t even notice.

Now I’m 56. 50 years into this journey with T1D, I don’t seem to have any complications of diabetes.

I attribute a huge part of my success with diabetes to the fact that when I was diagnosed, my whole family became diabetics. My mother completely changed how she cooked. No sauces, nothing fried. Broiling and baking became the Davis family’s cooking style. I recall we still had cakes for birthday parties, but people would make special desserts for me. If anything, I would have very small pieces, razor blade slices. My parents made it my disease, not theirs. I had to give myself insulin. My dad would just wait with me, even if it took 45 minutes. They would encourage me. But it was always my responsibility. They included it in our lives but did not make life about my diabetes. My parents’ approach to normalizing life with diabetes quite possibly made the biggest impact on me.

When I was young. I was hospitalized almost annually, every spring for a few days, because my glucose and insulin were so out of control. I have not been hospitalized since 2000, and before that, it was 1994. In the last 30 years, I have only been hospitalized twice. The power of knowledge, as a person with diabetes, has allowed me to stay out of the hospital. In the past, that knowledge just wasn’t there. And that’s from the progress and the tools. And it’s so empowering. I have confidence that I will be fine, and I can manage it. And I know I can go to the hospital if I need, but I haven’t had to in over 20 years.

I have been involved in JDRF in many ways – from being on the local board, many galas, Rides, Walks, raffles. I’ve had the opportunity through JDRF to meet people with T1D around the world. I’ve met Senators, PMs, MPs, and met so many families who have been touched with diabetes, from all around the world and all walks of life. All of us brought together by a common cause. And it’s such a powerful community. Truly, my involvement with JDRF is the silver lining of my diagnosis. It’s brought these incredible people into my life. Positive people with a passion for making a difference. Not letting fate happen but trying to change fate.

The complications of diabetes weren’t risks when I was diagnosed, they were inevitable. That was not good enough for my parents. They didn’t want to let that happen. Which is why my family got together with other families to start the Winnipeg chapter.

JDRF and the research that it helps to fund, has led to incredible research progress on so many fronts: cures, prevention, and treatment. Insulin analogs, blood testing, glucagon, HBA1c tests were not even thought about when I was first diagnosed. They were theories, ideas.

Now I wear devices that communicate with each other and decide based on sensor glucose reading how much insulin to deliver to me. And in a full circle moment we are back to no finger pricks. This has allowed us to take advantage of societal changes around labeling and health consciousness which make carb counting and enjoying sweets more manageable.

Today, we have so much more information. My pump tells me where my sensor glucose is all the time and what percentage of the day, I am in my target range. What my doctor would have given to know that 50 years ago. But there is a downside – more information gives me more to think about. I think I might spend more time thinking about my diabetes today than ever before. And it can be frustrating: seeing my sensor readings going up or down causes me to want to “fix” them. But I have to wait and see how the insulin on board interacts with the food I ate or wait for the juice I drank to get into my system.

The worst two hours of my life as a person with T1D was when I thought my daughter might have T1D. She was acting oddly, we were having a bad parenting/kid day, so I tested her blood glucose, and it was high. There is only one reason for a high blood sugar: diabetes. I phoned the DEC (Diabetes Education Centre) who I knew because of JDRF. I phoned the doctor, got her voicemail, and as I waited for her to call me back, my life flashed before me. All the things I had been through. I didn’t want any of that for my child. That was a real moment for me, I had never realized how hard it is to be a parent of a child with diabetes until then. Fortunately for me (and for Sophie) when the doctor called, she told me to wash Sophie’s hands and test her again. We did. Her sugar was normal. It turned out that when I had tested her the first time there was some honey on her finger and that was what caused the high reading.

The thing I’m most looking forward to from JDRF’s research agenda is prevention because another of my daughters has almost all the antigens for T1D. Fortunately she has not yet been diagnosed with T1D. Also, if we can prevent it, it’s (having type 1 diabetes) done. In the Cure pillar, immune tolerance is the most interesting part for me. Because I am still healthy, a cure would have to be a treatment without immune suppression to be a path I would consider.

I can’t imagine my life without JDRF. I would miss the community, the enthusiasm of everyone involved and the common purpose. I am immensely thankful for my 50 years with them. Nonetheless, I am looking forward to the challenge of living without the JDRF community because it means we will have found a cure for type 1 diabetes.